The Engineer's Middle Path

The Buddha was a Programmer too

Today, I want to take a leaf out of the teachings of the Buddha, specifically the concept of “The Middle Path”.

In the modern world, people have become increasingly obsessed with doing more. In every sphere of life possible. To the point that society actually frowns upon concepts like mediocrity and balance, which I think are not inherently evil and may actually allow us to focus more on what really matters.

What is The Middle Path really, and what do we stand to gain from implementing it in our lives?

Life as a zero-sum game

The terminology is from a very useful branch of mathematics called ‘Game Theory’. Now, even if you are not well-versed in this (I am not), it is not hard to understand.

Let us take a scenario where two competitors take part in a battle. Let us assign a score of 1 to the winner and a score of -1 to the loser. The sum of their scores, therefore, is zero. If it is a zero-sum game, the total score has to stay a constant 0. This means that if one wins, the other necessarily has to lose. Both of them cannot win, as the sum will be 2, greater than 0.

Too many people go about treating life like a zero-sum game. In other words, they think that in order for them to advance in life, someone else has to get behind in life. Conversely, if someone else achieves something good, they actually take that situation, which, mind you, is completely out of their control, as an indicator that they are getting behind in life. I don’t need to spell out that this is a very poor way to live and also a very stressful one. It means you must constantly think about everyone else scheming behind you, and you can never be genuinely happy for others.

For such people, there is only one way to get ahead in life: run faster than everyone else. And sabotage other people along the way. This is indeed manifesting in a toxic work culture, where it is more about just working all day and having no teamwork, as sharing knowledge with someone else may cause them to get “ahead” of you in life. This is true not just in a professional environment but also at home and in relationships both inside and outside the family. Unfortunately, many people have adopted this “win-lose” mentality.

A different approach

The other way to go about life is to see it as a positive-sum game. Other people’s gains are not your loss; we can all advance together. Moreover, what other people are doing in their lives is not under our control. We should care about what is up to us: living our own lives well. Of course, being too naive and innocent will lead to cunning people taking advantage of us, but being too cynical and suspicious of other people is not winning us any favours either. Instead, we must adopt the middle path, where we must balance our attitude towards everything in life. Excess of anything is bad; everything should be done in moderation.

The need to do more and be more comes from what I call a mindset of scarcity. This is a zero-sum mentality. There was a time when we needed to have this mindset, as the world was a very different and more unforgiving place up until the last few decades. I am not saying that we have solved all of the world’s problems; in fact, we are far from it, but you have to agree that the world of today is much better off (If you disagree, then reading The Better Angels of Our Nature by Steven Pinker will be a good start). Today’s problems are tackled more efficiently by a mindset of abundance, which is what comes to us when we start seeing life as a positive-sum game. And an important part of developing that mindset is adopting the middle path. Let us see through some more examples.

Before we move ahead, I want to clarify that I am not arguing that we should stop thinking about doing more and become sitting ducks. This is not an argument for nihilism, which is at the other extreme of the spectrum. What I want to demonstrate is ambition tempered by self-acceptance, the fact that mediocrity as a goal sucks but, as a result, is actually not so bad. We have to keep pushing ourselves, but we also need to have a healthy sense of self-compassion. Do you see how the middle path pops up here as well? It’ll show up a lot more now.

Not working vs working too much

Some people shirk work like anything. They will not do what is asked of them, and when they do it, it will not be on time, and the quality of work will be really poor. It’s as if they are begging you to fire them.

This is obviously bad, and I don’t recommend that anyone follow this approach. However, the logical extreme of this idea is as unhealthy, and unfortunately, it has become mainstream in today’s hustle culture. I am talking about putting in 14-hour workdays with too little sleep and too much coffee. People are working more and more endlessly to an end they do not know.

Examples of this abound in the world. It is ubiquitous, from big companies like Amazon and EY to small startups. When asked why they do this to themselves, people often justify themselves by telling others and themselves that they are being very productive and effective, that the whole project is riding on them, and that important people are counting on them.

Overworking, in fact, is also a form of indiscipline, an idea espoused by both Mark Manson and Ryan Holiday, who are the creators of the Subtle Art… and The Daily Stoic, respectively. Working too little is bad because it gets nothing done; too much overwork is just a form of escapism from deeper problems in life. I highly recommend checking out what they have to say on this topic.

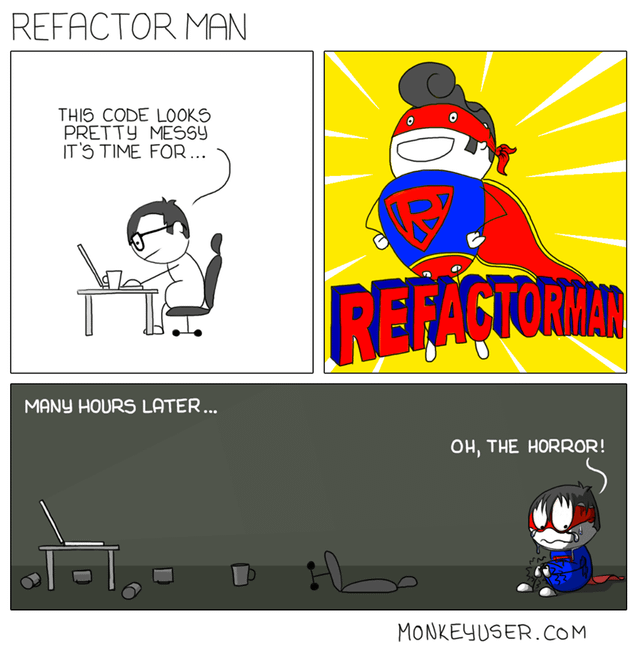

Refactoring in Programming

When it comes to programming, I found this article really nice in explaining my point.

When we begin to learn how to program, we are introduced to linear programs. Information flows from top to bottom without jumping back and forth in the middle.

Later, we get introduced to functions. It is easy to understand their advantage over normal linear programming. Even though the control flow becomes more complicated, the important parameters like reusability, scalability, etc all increase. Later, we learn about paradigms like Object-oriented programming, design patterns, and the factory method of programming, among a slew of other methods.

Each of them has its own pros and cons, but rigidly sticking to one method and applying it in every situation is not an efficient way to do programming. Too much emphasis on, let’s say, abstraction when it’s not needed makes it more complex and less efficient to write code that actually does the job.

On the other hand, not refactoring code at all is equally bad and makes the creation and maintenance of the program much tougher. There is a middle path or Goldilocks zone here also, a sweet spot that balances effort versus ease of maintenance. I highly recommend checking out Code Aesthetic to better understand this.

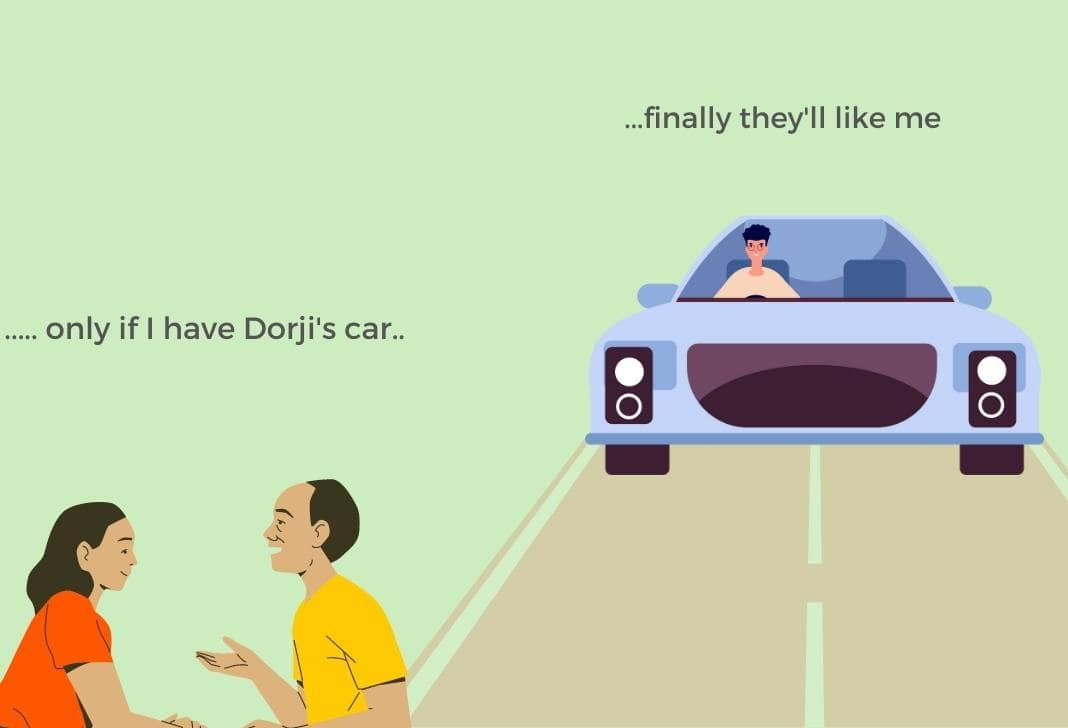

Man in the Car paradox

Morgan Housel first proposed this idea in his best-selling book “The Psychology of Money”. The name comes from a curious aspect of human psychology that Housel noticed in his childhood behaviour.

When he used to see someone driving a Ferrari or some other hot-shot car, he would imagine himself driving that car and getting recognition from people who would see him driving the car. The twist here is that when he looked at the car, he cared little about who was driving it. What he really liked was the idea of him driving the car because it would lead to admiration from others.

We often use wealth to signal our social status to others in society. That is one of the reasons why people can get so mad at accumulating more of it: what they really want is social recognition. However, as the man in the car paradox shows, other people really don’t care how much money you have; what they care about is the idea of having that money, paradoxically thinking that it would bring them much-deserved recognition from others.

The crux of the matter is clear: No one thinks as much about you as you think about yourself. If that is the case, then we are all running our own race. Whether I am ahead or behind doesn’t matter because no one is competing with me when I run my race. Others are too busy running their own races to take part in mine. Then why the frenzy to get to the supposed finish line? You are anyway gonna be the first one. On the other hand, not running at all is the actual loss, as then all progress gets stalled. We have to keep running, but we can always set our pace to our own choosing. This is the way of the middle path.

A way to resilience

Let us take the habit of planning for the future. There are two categories of people here: some people plan their whole lives to the last detail, while others cavalierly leave themselves entirely at the mercy of fate and are happy-go-lucky about life.

I believe neither of these two approaches is the best way to deal with life. If we want to be proactive and become the architects of our lives, it is important that we have at least an idea of where we are going and what our destination looks like. On the other hand, micro-planning every aspect makes us very rigid and brittle. Things seldom go our way all the time, and life comes at you fast.

It is much more important to be flexible here and to plan for our plan not going according to plan. The idea is to be anti-fragile, defined by Nassim Taleb as “things that gain from disorder”, and becoming more resilient is a big part of it. For that, we must embrace uncertainty while at the same time not throwing up our hands at the hopeless unpredictability of life.

Planning to every detail also has its uses, though. This is the approach for the hard sciences. NASA won’t be comfortable launching its rockets unless it has an exact idea of all the variables involved in the launch. However, in fields like psychology, which are not hard sciences, it is important to be resilient to change instead of denying it.

A Personal Example

I want to finish this by giving an example from my own life.

When I was in school, I was a very uni-dimensional person. I used to care about my studies and getting a good grade like mad, and that was all I cared about. Developing my personality and physical and mental health were all foreign concepts to me. In fact, I used to bring a book and pen to the field when we had PE class and spent the whole period just sitting there and solving problems xD.

During the time of COVID, this had visible implications. Not exercising at all meant that I, who was already overweight before the pandemic, now became morbidly obese, with my weight reaching 90 kg and my BMI shooting past 30. Even in this state, I was still focused on solving, preparing for the exams, and sitting all day with a big and fat book.

The body retorted, and just a simple fall, which at my age should not mean anything, was enough to create a hairline fracture in my ankle, and I had to spend a significant time on bed rest. The doctor was clear: the faster I shed this extra weight, the better it would be for me.

After I recovered, I became a different person. I walked several kilometres daily, controlled my diet, did proper exercise, and shed off around 25 kg in a year. Losing weight so fast brought its own set of problems, though; in the end, what worked was regaining some of it and maintaining it there. The middle path here again.

In addition, I cultivated several interests apart from just studying and became a much more multi-faceted and well-rounded person in general. I plan to keep it like this, as it is better for both my physical and mental health, as well as for developing my personality.

Conclusion

I hope that by this point, you are convinced that the middle path is literally everywhere in life if you know how to look for it. It is what I believe, and I hope that I could make you see as well, the cornerstone of a well-lived life, both in the professional and the personal sphere. A better way to deal with life is moderation in things. Everything in life should be given the attention it deserves.

A quote from Marcus Aurelius sums it up nicely:

The wise man accepts his pain, endures it, but does not add to it.

If you like what I am doing, this is a great way to show appreciation!