Open-source philosophy shares some interesting things with communism. A superficial glance, looking at only what you want to look at, will make you think that it indeed is a form of communism. I mean, just look at this Reddit post. Initially, I also used to think like this. But a much more thorough understanding of the OSS (Open Source Software) idea shows that it is much more capitalist-leaning than I originally thought.

The March Revolution

Richard Mathew Stallman (RMS) is considered to be the father of OSS. He is an American free software movement activist and the founder of GNU (Gnu’s Not Unix, it is a recursive acronym). However, his philosophy is a bit more general than OSS, called Free and Open Source Software (FOSS). In fact, the words OSS, OSI, FOSS, FLOSS, FSF, etc, will get thrown around a lot here, and it’s important to understand that technically, they are not interchangeable.

To make sense of this soup of acronyms, we will start at the beginning of how the March Revolution began, which is when RMS came up with the GNU Manifesto. To understand why he got motivated to do so, we must examine the backdrop in which this was occurring.

Back in the 1960s, software was expensive, and I mean, really expensive. Thus sharing source code for free was not something people even thought about. However, throughout the 1970s and 80s, the cost of computing kept coming down due to advances in hardware. Thus, in the 1980s, the concept of not sharing source code, or keeping it closed source, was becoming more of a hindrance than a help.

This was especially felt by RMS, who was working in the MIT AI Lab since 1971. Initially, a collaborative environment, by 1981, most of the software being used there, like the operating system, started coming from a company slapping proprietary licenses on it.

As the story goes, specifically, a printer from Xerox was not working as expected in the lab and would frequently jam. The previous printer had similar issues, and RMS had got around it by modifying the source code for the printer software to send alert notifications whenever it got jammed in order to solve the issue quickly. He planned to do the same with the Xerox printer but found that its source code was locked away. When he contacted Xerox to ask for the source code, they told him it was proprietary.

On top of all this, he found that a colleague at Carnegie Mellon University had the source code. But he also refused to share it, saying that he had signed a Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA) with Xerox. This infuriated RMS and was the final straw in kickstarting his revolution.

Not being allowed to tinker with the source code, being forced to sign NDAs, from Stallman’s perspective, was not helping our comrades. It was not just about one printer; for RMS it was a moral issue that companies were locking up software, turning programmers and colleagues against each other by making them sign NDAs, and rendering users powerless over their own computers. Software was becoming a tool of control rather than empowerment.

So he eventually resigned from the MIT Lab and started the GNU Project in September of 1983. The goal was to build a completely free Unix-like operating system, which would be completely homemade and free of all capitalist proprietary software. And he would give it for free to anyone who wanted to use it. He later published his ideas in the more detailed GNU Manifesto in March 1985.

In RMS’s own words,

Later I heard these words, attributed to Hillel :

If I am not for myself, who will be for me?

If I am only for myself, what am I?

If not now, when?The decision to start the GNU Project was based on a similar spirit.

This sounds like something Marcus Aurelius would say in Meditations.

Notice that RMS calls it “free” software, not “open-source”. There is an important distinction between the two, and we will get to it in some time.

Free Beers

People being people, they started taking liberties with the term “free software”. They took “free” as in free of price. That’s kind of like Stalin coming and saying that all comrades will get a free beer. Stallman and his comrades had to spend a lot of time clarifying their meaning of the word “free”. It is free as in free speech or free air, not free beers.

Stallman clarified that it had nothing to do with price. It is just freedom to use and modify the source code as one wishes. A great example is Red Hat Enterprise Linux, whose core product, Linux, is free software; they just charge a subscription for maintaining it on users’ systems. At the heart of it, what “free” means is that after all the business transactions have been done between the buyer and seller (which may or may not involve the transfer of money), the buyer cannot impose any restrictions on the seller regarding how the software is to be used. It now “belongs” to the seller, and they can do whatever they want with it.

In a sense, “free software” transcends money; it is an irrelevant question to ask. The term FOSS is sometimes called FLOSS (Free/Libre and Open Source Software) to make this clearer. The word Libre is a Spanish word that is means “free” in the sense of liberty. This makes it clear that this is about free as in free speech and is not about money.

To formalise this, and also to consolidate strength for his GNU project, RMS established the Free Software Foundation (FSF), which is a tax-exempt charity for free software development. As a shoutout, my preferred shell, BASH, was developed by an FSF employee, Brian Fox.

A Hurd of Linux

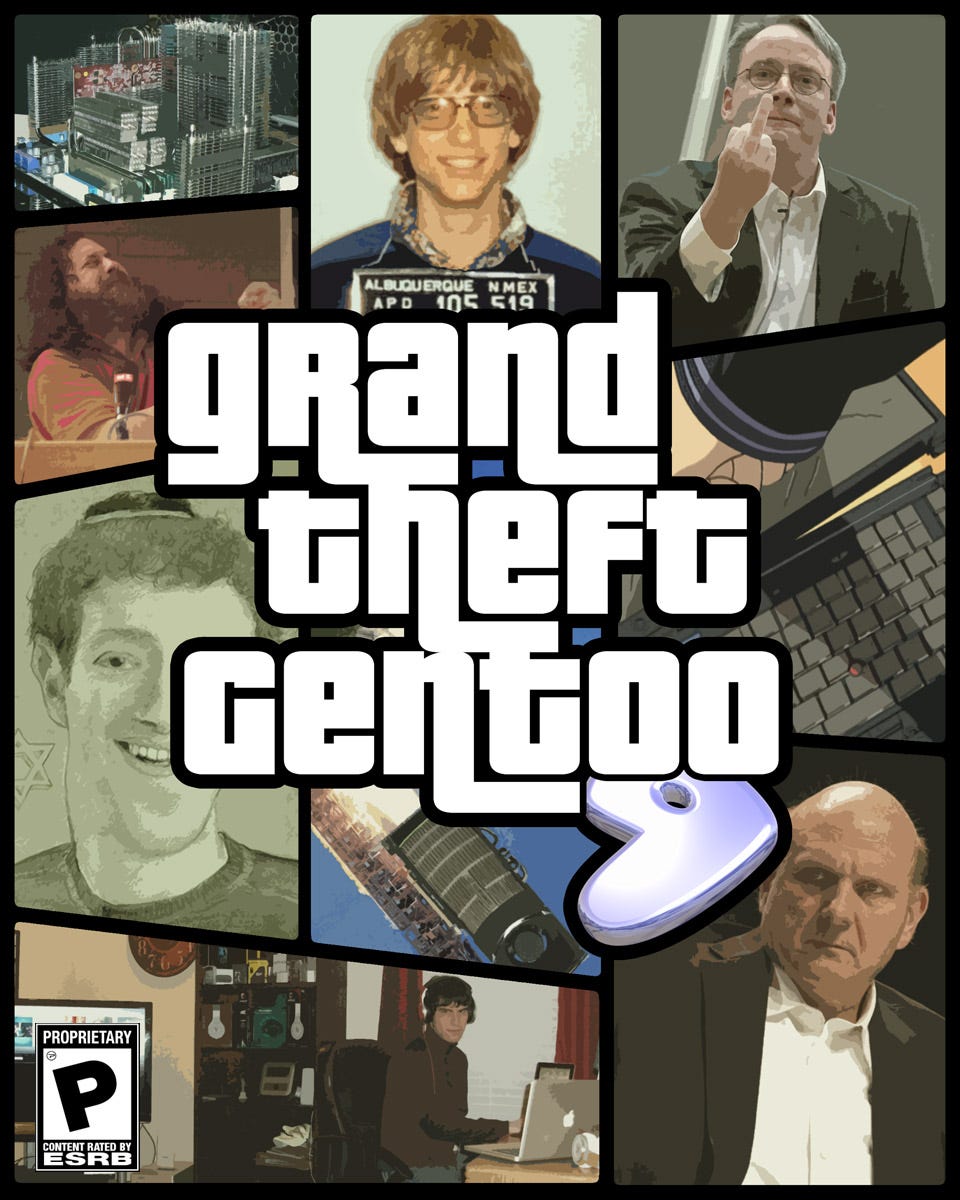

Any operating system needs two things to be useful: applications to run, and a kernel to manage everything. By 1990, a lot of applications, like the GNU Emacs, GCC, GDB, etc., were developed, and a kernel named GNU Hurd was under development. However, at this time, another revolution was underway, this time in Finland, by none other than Linus Torvalds and his eponymously-named Linux.

The development of the Linux kernel is very interesting in its own right and is covered in Linus’ autobiography, Just for Fun, but that is a story for another day. What matters is that it became the kernel of the GNU Operating System, and no one knows where the Hurd went to this day. RMS insists on calling it GNU/Linux or GNU + Linux, and indeed, modern distributions like Ubuntu, Fedora, Manjaro, etc, are powered by both the Linux kernel and GNU applications. But Linus is like “idc. kthx bye”. By the way, this more amoral attitude to software will recur again when we come to the difference between free software and open source software.

Interestingly, Microsoft considered Linux as their main competitor in the 1990s, and they used to frequently attack it and other OSS in general as “communist” in nature. Here is a poster released by them saying the same thing:

FOSS and OSS

So finally, here we are, at this difference between the more self-righteous free software philosophy by RMS and the more pragmatic open-source movement backed by Linus Torvalds.

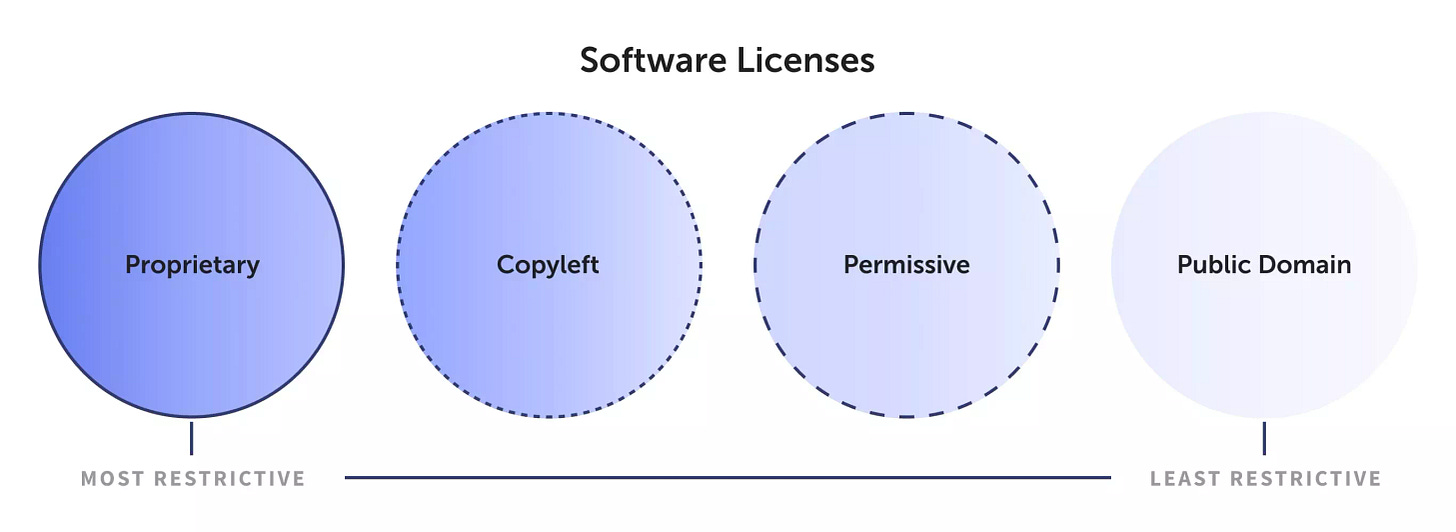

Notice the terminology that I used for both of them. FOSS is like a philosophy of user rights, stating that the source code is available and users are free to do whatever they want. OSS removes this latter restriction (or freedom, depending on your PoV), so software just needs to make its source code available. They don’t need to have a permissive or copyleft license (more on that later), so users might need to adhere to the company rules if they want to do something with the source code.

So in simple terms,

FOSS = OSS + Freedom guarantees

A good example of a software that is OSS but not FOSS is the Android operating system. Developed for mobiles, it is based on Linux and has its source code available to view, making it open source. However, it is not free, as the Android version that ships to most people uses certain proprietary components from Google, like Gmail, GDrive, Play Store, etc. Also, the “Android” label is trademarked by Google, and anyone wanting to use it has to meet certain requirements and get approval to use it. This is also why Librephone is a big deal.

OSS is less idealistic (and more practical imo) than FOSS. It is framed in a way that sounds less like “proprietary software is ethically wrong” and more like “this makes way for more collaboration and good software”. For big corporations like Google, Microsoft, OSS allows them to have the best minds work on a problem without facing questions of ethics or freedom. You could say that it’s just a hack or a shortcut, but you can’t deny that it’s a damn good one.

Linus Torvalds himself is a proponent of the OSS method. It is less about fighting a moral war and more about practical benefits like better code quality, security through transparency, collaborative development and faster innovation. It takes an amoral attitude, neither for nor against proprietary software. On the other hand, RMS refuses to use the term OSS, as for him, the ideology is not just about creating better software but about user rights.

So now that we have understood how this revolution began, it is time to see how exactly it is different from an established communist state.

Code Ownership

Normally, a piece of code is “owned” by its author or by a company. In the case of open source, there can be thousands of people working on a code base, so technically, everyone is an owner. So is everyone a comrade in a stateless societ,y then? Well, not quite.

A better way to look at ownership is through “licenses”, which decide what you can and can’t do with the code. Open-source licenses help developers share their software with the world while still protecting their intellectual property rights and controlling how it is used. It sets the ground rules for using and changing the source code.

There are two main types of open-source licenses: copyleft and permissive licenses. Copyleft is the literal antithesis of a copyright, in that it is basically a declaration that anything can be done with the code, as long as the result is also licensed under the same license. So you cannot take something like GNU, which is free under GPL, a copyleft license, do some modifications to the source code, and then market it as proprietary software.

Permissive licenses go even a step further and remove the restriction to use the same license for derivative works. This has a downside, though, that you can restrict the derivative of a free software to be proprietary. A great example is the X Window System, which was initially developed in MIT under a permissive license, but its derivatives used in Unix are proprietary.

So, in short, there is not much use in asking who the “owner” of a code is. It is more appropriate to ask who the original author(s) are. The level of ownership can be from committer to maintainer, and is generally based on merit and experience with the codebase.

A Moneyless Society?

In Marxist theory, a pure communist society is moneyless. Goods are distributed to everyone according to their needs. The OSS movement is disqualified from being communism by this condition alone.

OSS is not moneyless. Even RMS himself is not against a programmer wanting to be paid for their creativity. As iterated before, the “free” in FOSS is not about money. If you see the programs today, like Hacktoberfest, GSoC, etc., all of them are based on an incentive model. Programmers are incentivised to take part by goodies, bragging rights, or even actual stipend money.

Some of you might argue that in practice, none of the communist states became moneyless either. Money was always there, considered by many communists to be a necessary evil. But then, neither OSS nor FOSS is about a so-called state or collectivist society. They instead focus on the individual, and FOSS in particular is very intent on their freedom to see, change and distribute software as they wish.

The only similarity that they really share with communism is the emphasis on sharing and collaboration with others. But that is true of a lot of things, and in fact, it is the one thing that all communist states bungle up sooner or later.

The irony is rich: a capitalist, voluntary, decentralised system (FOSS) achieves the collaborative ideals that centralised communist states failed to deliver. The lesson might be that genuine collaboration requires freedom, not compulsion.

Conclusion

As you can see, though superficially similar, there is a wide chasm between the concept of Open Source and Communism. OSS is more similar to so-called “gift economies”, where people are rewarded (monetarily or otherwise) based on their work and contribution. RMS himself has actively rejected FOSS as a form of communism.

Nevertheless, the memes go on. As they should; they are, after all, our memes on our people. Glory to the OSSR!

Until next time.

If you like what I am doing, this is a great way to show appreciation!